|

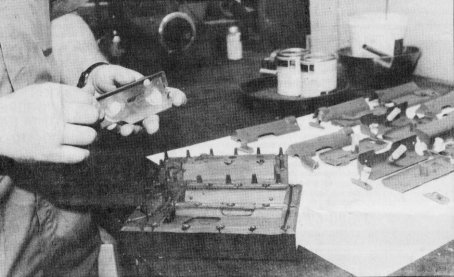

| Chris Greve in the machine shop he built near Covington. Greve and partner

Ron O'Connor build prototypes of machines for other area firms. PHOTOS By HARRIET BLUM |

FROM THE "MONEY" SECTION OF THE TIMES-PICAYUNE - Sunday,

June 5, 1988 SECTION G (New Orleans, La)

By THEO MULLEN Contributing writer

|

| Chris Greve in the machine shop he built near Covington. Greve and partner

Ron O'Connor build prototypes of machines for other area firms. PHOTOS By HARRIET BLUM |

| At age 32, Chris Greve has 24 years of welding and metal working experience.

For his eighth birthday, he asked his parents for a small welding machine. He promptly used it to fabricate a metal lathe and a band saw. "I used parts from my mama's washing machine, my old bicycle and metal road signs from the neighborhood," he said. With the band saw, the lathe and the welding machine he made go-carts and other toys, tools and symbols of boyhood. He had found his calling. Today, Greve operates out of a 2,700-square foot machine design and fabrication studio he built by himself among the tall pines of Covington. It is called Greve Technical Development, and it is a sophisticated shop of computers. plotters, electronic eyes operating mechanical metal cutters, huge metal lathes and other things. Most of the machines Greve designed and built. He often uses one machine to build another, larger and more complex machine. Businessmen and women come to him when they want something made that has never been made before, or when they want to improve existing machinery, but don't know how to do it.

Greve and associate Ron O'Connor brainstorm, design, draft, fabricate and assemble the machines their clients ask for. Often the finished product doesn't look anything like what the client had visualized, but Greve claims it usually works. Greve and O'Connor, however, don't think they're in the machine business but the creativity business. "The first question we ask a potential client is `Are you sure you need a machine?' " O'Connor said. "What we try to do is eliminate the need for us to design anything. If we can do that and make money for people, we know they'll come back and hire us again." Often, however, there's no way around designing a new machine.

Take, for example, the automatic hot stamp machine Greve and O'Connor just finished for a local plastic drinking cup company.

Making Mardi Gras cupsThe machine dramatically improves the production rate in stamping equipment that apply intricate foil stamped designs to plastic cups, the kind popular at Mardi Gras or in Las Vegas. Manually operated machines can produce only several hundred cups an hour and require the full attention of a worker. Greve's and O'Connor's automatic machine can print nearly 2,000 cups an hour; one worker can operate several machines. The thing looks like a huge insect slowly ingesting plain plastic cups and spitting out colorful completions. Greve and O'Connor designed it on a Hewlett-Packard computer and made it out of what looks like a 4-by-8-foot sheet of steel, some chain, several pieces of aluminum, a couple sheets of clear plastic, a few electrical connectors, a heating element and some elastic twine. |

|

|

| Greve looks over plans for quality control machine built for a Hammond company. | This rubber mold will be used to help manufacture medical equipment. |

| Of course, it is more complicated than that, but not to hear Greve talk:

"We try to make things dirt simple, taking the machines up to the point of

diminishing return. Usually we find that point where we solve 80 per cent

of the problem with 20 percent of the effort.....We try to build very practical

machines."

That practicality extends to Greve's studio and house, which share close to five acres outside Covington. The 3,000-square-foot house cost Greve $45,000 to build. He made it out of concrete and industrial materials. He used a process called tilt-wall construction. Sections of the walls are cast on the ground in a metal frame, then lifted into place with a crane. Greve, of course, built the crane. The angle of the house to the sun, size of window openings, amount of insulation and the like were all determined by a small analog computer Greve built to run a "finite element analysis" on the materials using several decades of daily weather data. The house will be earth-bermed to hold in heat and coolness, but already it is so well insulated by the thick concrete walls that only a 1.5-ton air conditioner is needed.

Electric bills are only $100Greve's monthly electric bills are about $100, including power used by the machine studio and the large electric-powered lathes and metal-working machines. "The concrete walls and slab pull coolness out of the ground in summer and hot during the winter, keeping the inside temperature usually in the 70s year-round," Greve said. "The air-conditioner is used mostly, to remove humidity from the air." According to Means Square Foot Costs, a manual professional builders use to estimate construction costs of residential and commercial buildings, the house should have cost about $150,000 too build. "I figure I paid myself about $100,000 to build my own house," he said. Not bad for a 9th Ward boy who grew up on Mazant Street near the Industrial Canal. Greve, a University of New Orleans graduate, lived with his parents until he got married because "it was the cheapest place to live." "There weren't any kids around to run the streets with when I was growing up. Only thing around was the public library, so I spent a lot of time there reading science books. I think that was part of what gave me the urge to build things," he said. While in college, a part-time job as a machinist and draftsman at American Marine Shipyard introduced him to "real world stuff, like big metal shapers and metal-milling machines," he said. After graduation from UNO in 1977 he became an engineer in the metal products department at Kaiser Aluminum Co.'s Chalmette works. He chafed under the rigid hierarchy of a large, unionized corporation. After several years, he left to "re-think" his future.

Machine design is careerA couple of free-lance engineering jobs later, he noticed there was no one around who could build machinery and handle all aspects of design, drafting, fabrication and construction. "That's when I realized machine design was my bag," he said. A stint as machine design engineer for the Laitram Corp. in Harahan reinforced that feeling. At Laitram, Greve was challenged daily by company founder and well-known inventor J.M. Lapeyre. "I was still in my early 20s when I answered an ad Laitram had in the paper for a machine design engineer. There was no way most people my age then would have had the experience necessary to do what they wanted done, but I knew I could do the job. I went through the interview process and finally met J.M. Lapeyre. He asked me just one question: `What is your hobby.' "When I told him it was metal-working in my own shop at home he said, `Good, the last guy we had said gardening and he didn't work out.'" Greve and Lapeyre are the co-holders of several patents, including one for a machine that fabricates wood and metal staircase stringers, a machine that prepares crabs to be automatically spiced and several others. An application fur a patent on a machine that automatically processes tuna fish has been filed with the U.S. Patent Office along with Chuck Lapeyre, one of J.M.'s sons. Several other patents are pending. He left Laitram in 1985 to build his house and studio (remember, he "paid" himself $100,000-plus to do the work) and launch his machine design business with O'Connor. It's working. He and O'Connor are regular design consultants to Laitram. Other clients include Try-Me Coffee Co., Sibling Cycle, Inc. and K and D Home Health Equipment Inc. Projects include a coffee weighing and packing machine; glass casting equipment (for glass sculptor Gene Koss of Tulane University); a highway reinforcing-mesh welding machine; an at-home pelvic traction device; devices for use by doctors doing microsurgery and several projects that are proprietary "We usually have to sign a confidentiality agreement, which means we can't even say what the project is -- that's how heated the competition is for developers of new projects," Greve said. Greve said he has since doubled his $35,000 salary at Laitram, and he thinks he and O'Connor could gross us much as $250,000 a year from the business. Recently Greve and O'Connor were retained by the UNO Small Business Development Center to evaluate the technical and practical aspects of the new products small business bring to the center for help with manufacturing and marketing. The pair advise on whether the product can be built safely and cheaply enough to make the business worth doing. "Most people are shocked to learn what it takes to develop a new product," O'Connor said. "It takes more than $200 and a letterhead. The patent alone costs between $2,000 and $3,000. And the cost of a prototype is much more." |

Link to related sites - [Future GTD HomePage] [old Greve Technical Development homepage]